Mindfulness for Stress Reduction

Would you like to reduce your stress? Very few people would say no to that offer! But what exactly does it mean?

We all have a sense of how stress manifests in our personal life and what we want to change. Many people would say they are looking for relief from the worries that plague them, while others might point to their stiff neck or tight jaw, or mention their headaches. However we experience it personally, stress impacts both our minds and bodies. It is a state of hyper-arousal where our minds and bodies are on alert, our adrenaline is flowing, and we feel a need to do something to protect ourselves.

What are some of the effects of stress?

In an aroused state, your body produces an adrenaline rush that increases your heart rate, elevates your respiration, tenses your muscles, and changes your blood flow. While this might be just what you need to complete a task or escape a dangerous situation, it might be not be a useful reaction to the current situation and could be counter-productive.

Under stress, you might find your thoughts racing in cycles you can’t escape. You might feel restless and anxious, unable to concentrate. You might become irritable, impulsive, angry, or aggressive. Over time, you might experience insomnia, reduced pain tolerance, and hyper-vigilance.

So it is helpful to know how to shift out of this aroused state to a relaxed state where your mind and body are at rest. Practicing mindfulness can provide that shift.

Sharon's story

The mother of two teenage girls, Sharon worked fulltime in customer service for a credit card company. Her days were spent talking to frustrated and sometimes angry customers, and her evenings were consumed with her daughters’ activities and dramas. In addition, Sharon’s parents were experiencing some health challenges and needed more help each week.

Sharon felt as though she was constantly putting out fires, with no control over where the next one might show up. She noticed that her neck and shoulders were constantly tight and sore and she was clenching her jaw. One day while stuck in traffic driving home from work, she started to scream with frustration at the car in front of her—and realized how wound up she was.

How does mindfulness help with stress management?

Most of the time, regardless of the situation we are in, there are a variety of ways to see and handle what is happening. Mindfulness gives us more options.

-

Paying attention protects us

To begin, the mindful practice of paying attention to the present moment helps us control the racing, repetitive, and non-productive thoughts that lead to stress. It allows us, in effect, to self-regulate.

To begin, the mindful practice of paying attention to the present moment helps us control the racing, repetitive, and non-productive thoughts that lead to stress. It allows us, in effect, to self-regulate.

For example, say you don’t get an immediate reply to an important text you send your partner. You might begin to worry that something has happened, get concerned that he or she is hurt, and then ruminate on all the possible things that could have gone wrong.

Consider instead how you could change your reaction by choosing to pay attention to what is really occurring in the present moment. Instead of becoming immersed in self-created thoughts and worries, you might just notice the desire for a reply and the arising concern. However, you wouldn’t react to or escalate those thoughts, but instead return to what you are working on at that moment.

This practice of paying attention to an experience as it unfolds is not the default mode for most people. We tend instead to spend much of our time reacting to events and spinning out explanations, implications, and stories—all of which often create stress. Paying attention allows us to cultivate a more direct experience of what is happening and nothing more. -

An open attitude provides relief

Another aspect of mindfulness is an attitude of curiosity and acceptance to whatever is occurring. In our example, when you don’t get a reply to your text, you could accept that there may be many reasons why. You might be curious as to whether your partner thought the text was as important as you did.According to psychologist Scott Bishop, who has researched the impact of mindfulness on our mental wellbeing, the practice of paying attention with an open attitude leads to a decrease in rumination and avoidance strategies, both of which underlie anxiety. An open attitude leads to a greater acceptance of what is happening, improved ability to tolerate difficult situations, and a lessening of reactivity and repetitive negative thinking

-

Mindfulness creates a new relationship to experiences

According to some psychologists, the core mindful practices of intention, attention, and attitude lead to a fundamental shift in perspective they “reperceiving.”

Reperceiving allows us to dis-identify from thoughts, emotions, and body sensations as they arise, and simply be with them instead of being controlled or defined by them. We realize, “this worry is not me,” or “these thoughts are not me,” which cultivates the ability to see a situation as it really is.

As we do this more and more, our confidence in our ability to cope grows, and we are less likely to become stressed by events that would have previously felt like a threat.

Try STOPping

STOP is an easy way to practice being mindful in the face of stress. When you notice something has triggered you and you are about to react, follow the steps below:

Slow down

Take a breath

Observe: what are you feeling in your body? What are you thinking? What other possibilities exist?

Proceed, considering multiple possibilities

It helps to bring an attitude of kindness to this practice, accepting your thoughts and feelings as they are. It also helps to bring curiosity to explore the situation with new eyes and an openness to new possibilities. To whatever arises, ask yourself: Could it be OK?

You can practice this in small moments, developing skill that will serve you well for more challenging “crises.”

What is happening in the brain?

There is a growing body of research examining what happens in the brain during and after meditation. This evidence consistently demonstrates that practicing mindfulness changes the structure and function of parts of the brain associated with emotional control.

This corresponds to behavioral studies done with experienced meditators, where results indicate that mindfulness practice enhances the ability to self-regulate attention and emotion.

How mindfulness impacts the brain

Response to threats

The area of the brain associated with the threat response, the amygdala, is smaller in meditators, while the area of the brain associated with thoughtful responses—the prefrontal cortex—is larger. These changes suggest that that mindfulness lessens reactive, fearful responses that enhance stress.

Mindfulness decreases

In addition, according to Dr. Richard Davidson, researcher and founder of the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, mindfulness increases the rate at which the amygdala comes down from high alert after a perceived threat. Mindfulness doesn’t prevent the amygdala (threat) response, but the response is shorter lived. The speed of recovery is associated with the amount of practice.

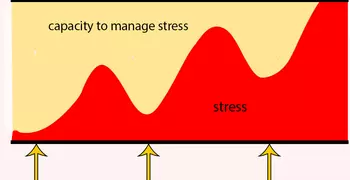

This is especially useful when we encounter a series of perceived threats, because if we have not fully recovered from one threat, we are already at an elevated state when another arises, and we reach overload faster, as shown in the graphic below.

Mindfulness helps us recover in between triggers, so our level of stress does not build.

Regulation of emotion

The hippocampus is another area of the brain that changes after mindfulness training. This part of the brain is believed to be involved in the regulation of emotion.

Following an MBSR course, participants showed an increase in the density of grey matter in the hippocampus, which may reflect improved emotional regulation and a perceived reduction in stress.

More changes

A growing body of neuroimaging research shows increased connectivity in the brain regions involved in attention, emotional control, emotional processing, and self-awareness.

What is the evidence for mindfulness for stress reduction?

There is an emerging body of evidence that suggests that mindfulness is effective for relieving anxiety and stress.

A 2014 review by Sharma that specifically looked at the impact of mindfulness for stress reduction found that “Of the 17 studies, 16 demonstrated positive changes in psychological or physiological outcomes related to anxiety and/or stress.” Despite the limitations of some of the studies, which included smaller sample sizes or no control group, the authors conclude that “mindfulness-based stress reduction appears to be a promising modality for stress management.”

A recent systematic review in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found “meditation programs can result in small to moderate reductions of multiple negative dimensions of psychological stress.” This might not sound too exciting. However, the authors go on to state that the effects of a mindfulness meditation program are similar to the “use of an antidepressant in a primary care population but without the associated toxicities.” In other words, mindfulness meditation programs have a similar effect as antidepressants, which are often prescribed for anxiety. And this is actually very exciting—the safe practice of mindfulness can demonstrate similar effects to more risky/less tolerated antidepressants!

Other reviews published in the last two years consistently report that mindfulness meditation has a positive impact on anxiety and stress.

Practice for greater resilience

Create mini mindful moments

You can do these easy strategies as you go about your day.

Create Mini Mindful Moments

- When waiting for the microwave to heat up your food or the printer to spit out your copies, look out over the room and pay attention to your breath as it flows in and out.

- Try mindful walking when you are running an errand, paying attention to the body as you move and place your feet.

- In moments of difficulty, take three mindful breaths. This is easy to do—no one needs to know you are doing it and it doesn’t take any time—you have to breathe anyway!

- Begin each meeting by coming back to your body, noticing the sensations of sitting and breathing. Then bring an intention to practice an attitude of curiosity and acceptance to whatever is occurring.

Deep belly breathing

This 5-min guided meditation can be deeply relaxing.

Body scan or sitting meditation

If you have 10 or 20 minutes, try one of these guided meditations.

Learn more

Free webinar

Learn how mindfulness can help in challenging times in our free webinar with Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) instructor Mariann Johnson.

Bishop, S. (2004). Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, V11 N3.

Brewer JA, Worhunsky PD, Gray JR, Tang YY, Weber J, Kober H. Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(50):20254-9.

Chiesa, A., Serretti, A. (2010). A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychological Medicine; 40(8), 1239–1252.

Farb NA, Segal ZV, Anderson AK. Mindfulness meditation training alters cortical representations of interoceptive attention. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013;8(1):15-26.

Farb NA, Segal ZV, Mayberg H, Bean J, McKeon D, Fatima Z, Anderson AK. Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2007;2(4):313-22.

Fox, K.C., Nijeboer, S., Dixon, M.L., Floman, J.L., Ellamil, M., Rumak, S.P., et al. (June 2014). Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews; 43, 48–73.

Goldin, P., Gross, J. (2010). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion; 10(1), 83-91.

Gotink R., Chu P., J., Benson H., Fricchione G., Hunink M. (2015). Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One. 16;10(4):e0124344.

de Vibe M, Bjørndal A, Tipton E, Hammerstrøm KT, Kowalski K. (2012). Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life and social functioning in adults. Campbell Systematic Reviews.

Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma, R, Berger Z, Sleicher D, Maron DD, Shihab HM, Ranasinghe PD, Linn S, Saha S, Bass EB, Haythornthwaite JA. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 174(3):357-68

Gu , J. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review 37: 1–12

Hempel S, Taylor SL, Marshall NJ, Miake-Lye IM, Beroes JM, Shanman R, Solloway, MR, Shekelle PG. (2014). Evidence Map of Mindfulness. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. VA-ESP Project #05-226.

Hölzel, B., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S., Gard, T. & Lazar, S. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Neuroimaging; 191, 36-43.

Hölzel, B, Lazar, S., Gard, T, Schuman-Olivier, Z. Vago, and Ott, U. (2011b) ‘How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective’. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 6: 537 DOI: 10.1177/1745691611419671.

Holzel BK, Ott U, Hempel H, Hackl A, Wolf K, Stark R, Vaitl D. Differential engagement of anterior cingulate and adjacent medial frontal cortex in adept meditators and non-meditators. Neurosci Lett 2007;421(1):16-21.

Holzel BK, Hoge EA, Greve DN, Gard T, Creswell JD, Brown KW, Barrett LF, Schwartz C, Vaitl D, Lazar SW. Neural mechanisms of symptom improvements in generalized anxiety disorder following mindfulness training. Neuroimage Clin 2013;2:448-58.

Kilpatrick LA, Suyenobu BY, Smith SR, Bueller JA, Goodman T, Creswell JD, Tillisch K, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. Impact of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction training on intrinsic brain connectivity. Neuroimage 2011;56(1):290-8.

Khoury B., Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, Chapleau MA, Paquin K, Hofmann SG. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev.; 33(6), 763-71. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005.

Lutz A, Brefczynski-Lewis J, Johnstone T, Davidson RJ. Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: effects of meditative expertise. PloS one 2008;3(3):e1897.

Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Astin, J. (2006). Mechanisms of Mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 62(3), 373–386

Sharma M., Rush SE. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: a systematic review. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med.;19(4):271-86.

Tang YY, Ma Y, Fan Y, Feng H, Wang J, Feng S, Lu Q, Hu B, Lin Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhou L, Fan M. Central and autonomic nervous system interaction is altered by short-term meditation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106(22):8865-70.

Taylor VA, Grant J, Daneault V, Scavone G, Breton E, Roffe-Vidal S, Courtemanche J, Lavarenne AS, Beauregard M. Impact of mindfulness on the neural responses to emotional pictures in experienced and beginner meditators. Neuroimage 2011;57(4):1524-33.

Wells RE, Yeh GY, Kerr CE, Wolkin J, Davis RB, Tan Y, Spaeth R, Wall RB, Walsh J, Kaptchuk TJ, Press D, Phillips RS, Kong J. Meditation's impact on default mode network and hippocampus in mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Neurosci Lett 2013;556:15-9.

Zeidan F, Martucci KT, Kraft RA, Gordon NS, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC. Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. J Neurosci 2011;31(14):5540-8.

Zeidan F, Martucci KT, Kraft RA, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC. Neural correlates of mindfulness meditation-related anxiety relief. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2014;9(6):751-9

Ziv M, Goldin PR, Jazaieri H, Hahn KS, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder: behavioral and neural responses to three socio-emotional tasks. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 2013;3(1):20.