What Is the State of the Evidence?

The research on mindfulness is booming. A search for the word mindfulness in Google Scholar yields over 355,000 results! In one month alone, the Mindfulness Research Journal reported on 48 new studies.

The research on mindfulness is booming. A search for the word mindfulness in Google Scholar yields over 355,000 results! In one month alone, the Mindfulness Research Journal reported on 48 new studies.

But with all this research--and surrounding media attention--there are issues and questions. It is not always clear what these reports consider “mindfulness”: what are these people actually doing? And some reports ignore the complexities of the mindfulness research or draw broad conclusions that aren’t justified. So let’s take a closer (and realistic) look at mindfulness research.

Types of mindfulness research

Here are some pieces of the research explosion:

- Researchers are conducting randomized control trials—the gold standard for assessing effectiveness of a treatment—and testing the impact of mindfulness programs against standard of care or other treatments for various symptoms or conditions.

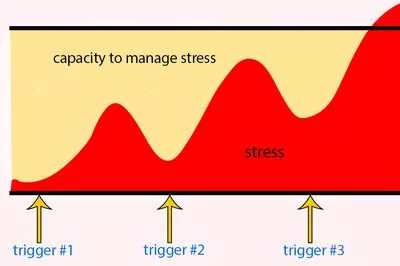

- Other researchers are analyzing possible mechanisms that might explain why mindfulness helps, looking at behavior as well as biological measures, such as heart rate.

- Neuroscientists are exploring the impact of mindfulness on the structure and function of the brain using imaging techniques such as fMRI.

- There has been an explosion of summaries of the research with major systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in journals such as the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and Cochrane Reviews.

Where is there good evidence?

Read more about the benefits of mindfulnessConsensus is emerging on the effectiveness of mindfulness for specific conditions, in particular:

- Depression, stress, and anxiety

- Pain, specifically in alleviating the psychological experience of pain

- Overall health and wellbeing

- Performance

What are the limitations of the research on mindfulness?

Common limitations of the research on mindfulness include:

- Many of the studies done on mindfulness are not randomized control trials (RCTs), or they compare mindfulness to a passive control, such as a waitlist, rather than an alternative treatment, so the results only indicate that mindfulness is better than waiting.

- Many studies have small sample sizes or are pilot studies. This means that new, better quality studies might change the conclusions.

- Participants in the studies are more likely to have already tried meditation and come into the study believing in the results of meditation, which may bias their results. While that isn’t a bad thing, it means we don’t always know how meditation might work on those new to it, or those who are skeptical.

Other issues with mindfulness research

The mindfulness practice

One important limitation concerns the mindfulness practice itself. While many articles study the impact of a standardized program, usually Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), others are less specific about what the mindfulness intervention was or the training of the instructor. This opens the possibility of an ineffectively taught program, or students with limited practice time, which could lead to an underestimation of the effectiveness of mindfulness.

Even MBSR differs with each individual instructor. Moreover, MBSR was developed to help patients deal with pain and psychological distress caused by a health condition, and as such, may not be an appropriate program for studies assessing other outcomes, such as enhanced performance or general wellbeing.

How it is measured

There is debate about how to measure what it means to be mindful. There are a number of measurement tools in use, but some debate about their validity—are they measuring what they say they are? Does what they are measuring match the outcome being studied? A systematic review of tools used to measure mindfulness noted a number of problems with the measurement tools, including:

- Differences in the definition of mindfulness

- Lack of verification that participants understood the questions asked

- Dependence on self-report with no external confirmation or investigation of differences between self-report and external measurements (i.e., other people’s observations)

- Lack of distinction between participants valuing mindfulness versus actually practicing and increasing it

What is the bottom line about research on mindfulness?

In short, for some areas, such as depression and anxiety, the evidence for mindfulness is as good as the evidence for many standard medical treatments, with systematic reviews or number of high quality RCTs suggesting effectiveness. Other areas, such as substance use, eating disorders, smoking, multiple sclerosis, PSTD, mood disorders, hot flashes, and sleep have some supporting evidence, but there is need for more quality studies.

Overall, better quality studies are needed. This research should describe the mindfulness program in more detail, use measurement tools that relate to the outcomes being evaluated, adopt a randomized control trial format with active controls that compare mindfulness to the standard of care or another treatment, and include large enough sample sizes to be confident about the effect.

For some areas, such as depression and anxiety, the evidence for mindfulness is as good as the evidence for many standard medical treatments, with systematic reviews or number of high quality RCTs suggesting effectiveness.

Boccia, M., Piccardi, L., Guariglia, P. (2015). The meditative mind: A comprehensive meta-analysis of MRI studies. BioMed Research International; 2015, Article ID 419808.

de Vibe, M., Bjørndal, A., Tipton, E., Hammerstrøm, K.T., Kowalski, K. (2012). Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life and social functioning in adults. Campbell Systematic Reviews.

Eberth, J., Sedlmeier, P. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness; 3(174), 174-189.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E.M., Gould, N.F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., et al. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med; 174(3), 357-68.

Gu, J. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review; 37. 1–12.

Hempel, S., Taylor, S.L., Marshall, N.J., Miake-Lye, I.M., Beroes, J.M., Shanman, R., et al. (2014). Evidence map of mindfulness. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. VA-ESP Project #05-226.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V. et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev; 33(6), 763-71. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005.

Kok, B., Waugh, C., Fredrickson, B. (2013). Meditation and health: The search for mechanisms of action. Social and Personality Psychology Compass; 7(1), 27–39.

Park, T., Reilly-Spong, M., Gross, C. (2013). Mindfulness: a systematic review of instruments to measure an emergent patient-reported outcome. (PRO) Qual Life Res; 22, 2639–2659.

Sharma, M., Rush, S.E. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: A systematic review. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med;19(4), 271-86.