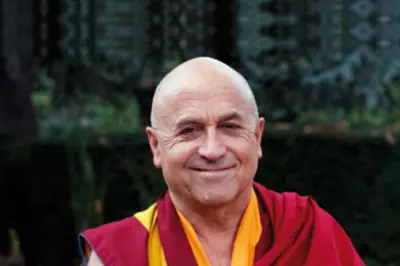

Interview with Matthieu Ricard

More than 35 years ago, Matthieu Ricard left a promising career in cellular genetics to study Buddhism in the Himalayas. After earning a doctorate in biology from the prestigious Pasteur Institute in France, Ricard left Paris and moved to Darjeeling, India to study with a great Tibetan master. Today, Ricard draws upon his recent writings, research into brain plasticity and cognitive neuropsychology, and his work with neuroscientists and Buddhist practitioners at the Mind and Life Institute (co-founded by the Dalai Lama), while examining the interconnecting relationship between meditation, brain circuitry, and emotional balance.

Will you briefly describe your background and area of expertise?

Ricard: I was born in France. My father was a renowned French philosopher and journalist, and my mother was a painter. So I grew up in Parisian intellectual circles. When I was 20 in 1967, I traveled to India, [after] having seen some documentaries on some great spiritual teachers…and I was very impressed by this encounter. So I went back and forth every summer for five or six years. And then in 1972, when I was 26, just after finishing my PhD from the Pasteur Institute, I left for good for the Himalayas, and now it’s [been] almost 40 years, and I’ve lived there happily.

From 1989 onwards, I’ve been serving for the Dalai Lama as his French interpreter. And then I got involved in science again in 2000 when a research program on the effect of meditation and mind training on the brain was started in various labs in Madison, Wisconsin; Princeton; Harvard; Berkeley; and now in Zurich and Austria.

What was your main inspiration for leaving molecular biology and moving to the Himalayas? Was there a person?

Ricard: Yes, of course—a spiritual teacher. Before, I [had] met quite extraordinary people. I had lunch with Igor Stravinsky when I was 16… [Some of the people I’d met] were wonderful people as human beings, and some people were more difficult. I could not see a correlation between their particular genius in playing chess and music and mathematics, etc. … with human qualities. Some were really good, wonderful people, and some were difficult characters, but there was no clear correlation. But when I met some spiritual masters, [I thought that] there had to be a correlation, and it turned out to be true. You can’t be at the same time a spiritual master and someone who is always angry. It doesn’t work.

It was the human quality of those remarkable sages and wise men [that] impressed me, and I thought, “This is for me, a source of inspiration, an exemplary life,” and I wanted to just spend time with them to benefit from their teachings, from their inspiration, from what they were. Often, they were a great part of the teachings. And after many years, I was very comforted that it was not just an appearance. Everything I could see over so many years has comforted me that really they were exceptional human beings and ….[good examples] of wisdom, of compassion, of loving kindness, and that really inspired my whole life.

You said you got back into science in 2000, with some of the research at Madison, Princeton, and other universities. Could you tell me more about that?

Ricard: The Dalai Lama has been extremely interested in science since his childhood. There were a group of people who thought we should facilitate his encounters with great scientists. So there was born the Mind and Life Institute founded by a remarkable Chilean-born neuroscientist named Francisco Varela and an American businessman named Adam Engle, and then many wonderful meetings occurred since then.

In the year 2000 in India, we had a five-day meeting about destructive emotions with the Dalai Lama and remarkable scientists [who studied emotions, psychology and neuroscience]. Midway through that meeting, the Dalai Lama asked, “What can we contribute to society?” And that’s when we came up with this idea of launching a research program on the effect of mind-training and meditation on the brain.

I participated from the very beginning [since I was] sort of between the two worlds, having done years of solitary retreats and having a scientific background. I was the first guinea pig and also helped the scientists to think about the scientific protocol to investigate the effect of meditation. And then of course, many other experienced meditators who had done between 10,000 to 40,000 hours of meditation joined. And now several high-profile scientific papers and journals have been published and have had a large impact on the scientific community about the effect of meditation that shows deep changes in the brain and in the ability to generate very powerful states and some brain waves (the gamma wave), which were so intense that they were not earlier observed in the history of neuroscience. [The studies] have been mostly focused on the meditation on compassion [and] meditation on focused attention. Those are two of several important types of meditations, but we cannot study everything at the same time.

This is really a driving new field that we can call contemplative neuroscience. Richard Davidson in Wisconsin is spear-heading that, but there are other labs that are [also] very much involved. In a few days at Harvard, we are having a one-day meeting with the Dalai Lama, and six labs are coming to report on their recent works [to] see if we can go one step further.

So this is all taking place right now as ongoing research?

Ricard: Yes, it is continuing. The NIH has been granting funds for the research. It is of strong interest because it shows dramatic changes, not only for those who did 40,000 hours of meditation, but even [for those who did] three months, half an hour a day. The research shows a significant decrease in traits of anxiety, tendencies to depression, a boost of the immune system, a reduction of cortizol that leads to stress, even blood pressure, using a very popular meditation technique called MBSR (mindfulness-based stress reduction). Three months of this training has been shown to lower blood pressure… in people who had high blood pressure…So there are remarkable findings... Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy can significantly lower the risk of falling back into depression… Relapses are reduced by about 30 percent…

We have known about the placebo effect for many years. This is a remarkable effect—placebo can cure 30 percent in many cases. Sometimes people look down and say, “Ha ha”—you give nothing, and you get cured. But in fact…instead of saying, “We fooled you,” we should say, “Look, we revealed the fact that changing your attitude has a curative effect… Maybe you can go directly to a change of mind, a change of attitude.” Teach that rather than treating people like kids and giving them placebos. That is what mind training is about. And mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) certainly has the same effect.

So you change your attitude and make it more positive. It doesn’t mean… “Oh, I’m going to be well for sure.” It should not be childish. You should really stop worrying, develop the real wish to live and with a good motivation, [such as] “I have a better life and I can put that life at the benefit of others.” I think if your direction in life is clear and if you develop the wish to accomplish/have a fulfilled life and to contribute something to others, I think that definitely gives you such a strength to want to be alive, that that would be the best placebo…

We vastly underestimate the power of transformation of mind. Placebos are like the lollipop of optimism, but we can do much better by dealing directly with the mind… And it works!

How do you think placebos, alternative medicine and Western medicine can all work together?

Ricard: When you see a Tibetan doctor taking care of a patient, first of all, of course there are many wonderful medicines that come from [there in the past] 2,000 years. But this doctor is usually so attentional, so kind, and so careful of what you really feel and then [he sees] you as a human being instead of running you through some quick tests. So that itself, the trust and confidence in someone that cares for you is of course so invigorating...that someone cares.

So the human aspect is much more present in these kinds of therapies. And I’m sure it accounts for a lot of its efficacy.

What would you suggest that people can do to improve or maintain their health, with regard to your experience with both contemplative science and Western science?

Ricard: I think it comes with developing some strength of mind…by the confidence that you can change your attitude. It’s not being discouraged, or always ruminating about oneself too much, and being overly concerned [with] always “Me, me, me, how I feel” every moment. This is a down-pulling attitude because you’re so concerned about how every small detail is going to affect you. This kind of self-complaining and paying attention to every little feeling leads to rumination about everything that happens, everything that’s going to happen…Then of course, you’re like a target for thousands of adverse occurrences.

If you take a little distance or openness or attitude or different perspectives…then it’s like, “Oh, a small thing happens somewhere in the landscape, okay, it’s there, but so what?” So then, it doesn’t affect you. It’s like a handful of salt. If I put it in this glass, it becomes undrinkable. So [it is with] a narrow-minded, self-preoccupation. But if my mind becomes like a big lake, then the same handful of salt doesn’t make much difference; it doesn’t make the whole lake salty. So just broaden your mind.

There’s a beautiful teaching in the Buddhist literature that the Dalai Lama often quotes that says, “If there is a remedy or a cure, a solution to a problem or difficulty, why worry?” There’s no need to worry. If there’s no solution, there’s no point to worry, because worry is always an extra burden. You get [something] in your body that is the suffering or the problem, and then you [add] a second one, which is worry. In both cases, [it is] pointless.

Just be free, and at least you will go through adversity with a stronger mind, and therefore, you’ll be less affected, and pain will affect you less. A big part of pain is the subjective reaction of trying to revolt against pain. If it’s there, it’s better to deal with it. Most of it is “I cannot stand it,” and that component is enhancing pain so much. The way you experience [pain] can change so much depending on your attitude.

In that sense, is the brain just like any other muscle that needs to be toned?

Ricard: That’s definitely simplified—comparing it to a muscle, but certainly, it can be trained. It is known to be trained when you practice anything, like learning a musical instrument, or a bird that learns a new song, or London cab drivers who have to memorize thousands of streets. Their brain changes in some areas. So whatever you train, you change your brain. You could train on the streets of London or playing the piano, or you could train on resilience, compassion, altruism, and attention. In a way, there’s nothing wrong with playing the piano, but it’s not a huge trauma if you don’t.. But if you don’t have altruism, inner strength, inner peace, attention, then it’s a trauma. It makes a difficult life for you and for others.

What is some of the latest research that you’re able to share with us now, specifically coming out of your work at Madison with Professor Davidson?

Ricard: One that was published a few weeks ago…shows that when you engage in compassion, and you hear a distressing sound, like someone calling for help, there is an activation in an area of the brain called the insular, which has to do with empathy and altruism, that is vastly more activated than in non-meditators. There is definitely openness to others’ suffering that is dealt not with distress but with compassion. That has been very clearly demonstrated. There are other papers on attention that have shown remarkable improvement in attending to a task after three months of meditation.

How would you describe the relationship among brain circuitry meditation and emotional balance?

Ricard: Meditation is about cultivating constructive emotions, like altruism, compassion, … [You] can dramatically change [your emotions] to be more altruistic, more loving, more compassionate, more attentive, and especially to have an inner sort of confidence and strength that you know that you have the resources to deal with whatever comes your way. You’re not insensitive or indifferent, but you’re also not vulnerable to the upheavals that cause emotional stress because you can buffer that… So that’s the result of meditation; you could call that emotional balance.

It can be a fearful thing for an average person to consider opening oneself up on a compassion level to the degree that they can really hear other people in pain.

Ricard: If contemplation of other people’s pain just increases distress, then I think we should see it in another way. If we don’t center too much on ourselves, then [we] increase our courage and our determination to remedy the pain, not our distress. If we have unconditional compassion, then it increases our courage. So that’s the difference, self-centered motivation versus altruistic motivation.

When you see those in healthcare who don’t get this burn-out, they are very motherly, fatherly, or loving and attentive with the patients. [These] wonderful caretakers, doctors, and nurses don’t get as much burn-out as people who are more defensive of the feelings and suffering of others...Too much involvement with one’s feeling [is destructive]. If they have too much self-centered feelings, they get in trouble.

I know you have been involved with a lot of humanitarian work. Could you tell me about that?

Ricard: At some point, a publisher proposed that I do a book of dialogue with my father. I was quite surprised. I thought he would never do it, but he accepted. So then I got worried because he’s known to be a relentless sort of thinker, but it went very well. He came to Nepal, we had ten days of talk, and we came out with this book called The Monk and the Philosopher, which was really a transcript of this dialogue. And just in France, it sold almost half a million copies. So suddenly, some resources came my way, and I didn’t see myself buying a house with a swimming pool or a car. So since then, I’ve dedicated the entirety of my royalties of my books to a foundation. Then some philanthropies joined us. And now we have 30 humanitarian projects—education, health, schools, and clinics in Tibet, Nepal, India, and some in Bhutan. I do that with my monastery, Shechen, where I live in Nepal, together with volunteers and philanthropists, and we have a website, www.karuna-asia.org, where you can find more details about those projects.

What is next on your agenda?

There are tragic events in Tibet now. That’s been the harshest situation in 20 or 30 years… It’s a terrible situation, and the Chinese Communist government is cracking down in a very brutal way. So I don’t know. We hope to continue our projects, but it’s not easy. And then we have a [humanitarian] project in Nepal that is a big involvement for me. And then the science research—I’m going to continue to help… And so basically, this research is going to go on, and I’m happy to participate. I hope it will help to lead to a more compassionate society.