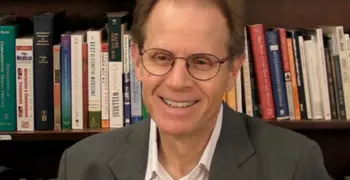

2 Gratitude Practices That Enhance Your Wellbeing With Esther Sternberg

Key points

- Gratitude practices enhance brain regions supporting social interactions and interpersonal relationships.

- A better way to reduce stress than reducing the negative is by enhancing the positive with gratitude practice.

- Start the day turning east, west, north, and south, feeling grateful for everything you see, hear, and feel.

This blog post was first published just before Thanksgiving 2023, in my regular Psychology Today blog “Creating Wellbeing Wherever You Are”. To my surprise it quickly garnered close to thirty thousand views. That told me something: people are craving ways to feel grateful, even in the darkest, scariest times.

The blog post is a condensed version of parts of the Spirituality chapter in my book Well at Work: Creating Wellbeing in Any Workspace (Little, Brown Spark 2023), based on my more than two decades of research using wearable devices to measure the impacts of office environments on physical health and emotional wellbeing. I started this research while I was at the National Institutes of Health with colleagues at the U.S. General Services Administration, and we continued to work with together after I moved to the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona. Being at the Center gave me a fresh perspective, which allowed me to understand the data we were gathering in the framework of integrative health. It became clear to me that the ideal workspace – indeed any space in which you live, or work, or learn or play, could be designed to enhance each of the seven domains of integrative health. Doing so would enhance resilience and keep people happy, healthy, and productive.

Ceremony for Earth, Big Sur, California

Source: Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock

When I was writing the book, my editor suggested that I include chapters on how to embed each of the seven domains of integrative health into an ideal workspace. As defined by the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine, those are: sleep, resilience, environment, movement, relationships, spirituality, and nutrition. It was easy for me to write about six of the seven, but at first, I couldn’t figure out how to write about bringing spirituality to the workspace. What is spirituality, anyway? It turns out that there are many elements of spirituality that can help one achieve one’s best work, no matter what the task. Flow and being in the zone are akin to meditation. Teamwork requires compassion, empathy, and healthy relationships. That’s where gratitude comes in. It helps to be grateful for the help of your colleagues, mentors, mentees, in short everyone with whom you work.

I asked one of my colleagues at the Center, Dr. Robert “Rocky” Crocker, who had been instrumental in defining the seven domains of integrative health, how he would define spirituality. That’s when he described his moving gratitude practice, which he learned from his Choctaw grandmother. He shared that it helps him start every day centered and ready to face whatever challenges might come his way.

I can’t think of another country whose origin story is so deeply intertwined with gratitude as the United States. In Canada – specifically in French Canada, we did celebrate Thanksgiving – a month earlier than Americans do, presumably to coincide with the earlier harvest. But it was not the massive holiday it is in the U.S. Millions of people didn’t displace themselves across the country, fighting crowded airports and highways, to share a meal with family.

The French-Canadian word for Thanksgiving is “le jour de l’action de grâces” — literally translated as actions of grace, coming from the heart, and expressed in words or actions. The term has a religious origin in the Bible. Indeed, most religions at their core include gratitude – grace before meals, gratitude in prayers, thanks for bountiful harvests.

While several countries around the world — 17 at this time, have adopted Thanksgiving as a national holiday, it is not, as it is in the U.S., part of the nation’s DNA. Except it is for some native American nations whose traditions the early European settlers displaced. What can we learn from those traditions, to enhance our well-being?

*According to Dr. Robert (Rocky) Crocker, an integrative medicine practitioner and director of strategic partnerships at the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine, respect for all and respect for the sacred in all is inherent in the practices and understandings of many indigenous peoples, including Native Americans, Canada’s First Nations, and the aboriginal people of Australia. He should know — his grandmother was Choctaw whose forebears had been forced off their land in Mississippi by President Andrew Jackson in the 1830s and marched to the dust bowl of Oklahoma, in what became known as the Trail of Tears. While Crocker was not raised in his ancestors’ traditions, he rediscovered them in adulthood after a period of severe job-related burnout.

Source: Wikipedia By Phil Konstantin

There is a mound in east central Mississippi called Nanih Waiya, which the Choctaw venerate as the birthplace of their people — the place where their people first emerged from the earth. Crocker had had a transformational experience there as a child: when on crutches for a leg ailment, he labored to climb to the top of the mound and was awed by what he saw all around him.

As an adult, he revisited that mound and had a similar experience. He then spent a year reading everything he could to learn about spiritual traditions — the Bible, Native American and Buddhist traditions — and, surprisingly, also about quantum physics. From these learnings he drew the spiritual practices with which he now starts each day and carries with him throughout every one: There is respect and being mindful of the sacred in everything and everyone. There is a knowing of the interdependence among us and everything and every person around us; what happens to one person or part of creation affects everyone else. There is the responsibility to leave the sacred altar of the earth better than how we found it. And then there is gratitude.

Crocker now starts each morning outdoors in a spiritual practice that helps him enter the world mindfully, facing north, south, east, west, above, and below, and feeling gratitude and connectedness with nature and everything and everyone in it.

The practice of gratitude has echoes in many traditions. In Jewish observance, a prayer is recited every morning thanking God for awakening, and blessings are recited at the start and end of every meal to thank God for providing food and sustenance. In Christianity, a similar gratitude prayer — the ritual of saying grace — starts every meal. Gratitude practice is so embedded in Western culture that it is at the core of one of Americans’ most beloved holidays. Gratitude is also reflected in the old adage “Count your blessings” — immortalized by Bing Crosby’s deep baritone singing Irving Berlin’s “Count Your Blessings (Instead of Sheep)” to Rosemary Clooney in the 1950s movie White Christmas: “When I’m worried and I can’t sleep, I count my blessings instead of sheep.” This also happens to be good advice; counting my own blessings — the things I am grateful for — certainly helps me when I’m feeling worried and have trouble falling asleep.

Yet how many of us take the time to intentionally feel gratitude on a regular basis? If you can’t find a moment or a place to do this in the middle of a busy workday, try stepping outside before you start your day and taking a moment to look all around you. Take in the horizon, the larger and smaller things you see — a tree, a leaf, the reflection of light on the leaves or on a building’s windows and doors. Feel the crunch of gravel or the smooth pavement under your feet and the brush of wind on your sleeve. Listen to the rush of traffic or the birds chirping. Breathe deeply and slowly. Try to consciously feel gratitude for all that is around you and for all the people in your life who are meaningful to you, including those at work.

What this gratitude practice is doing is enhancing brain-heart connections, moving your stress response back along that rainbow curve of the stress response and performance. At the same time, gratitude practices enhance brain regions subserving social interactions and interpersonal relationships, and feel-good dopamine reward and anti-pain endorphin pathways. All of which reduce the stress response, allowing you to start the day at a calmer place so that when the stresses of the day do hit, you won’t fall over the edge into anxiety and distress.

From the brain’s point of view, enhancing the positive is a more effective way to reduce stress than trying to reduce the negative. Once, on a panel I was moderating, the Dalai Lama told me that stress is not a word in the Buddhist tradition. I asked him why, then, did he meditate. His answer: meditation was a path to love and compassion.

I think I learned my breakfast ritual from my father, who, when the weather was fine, would take his breakfast outdoors on our terrace overlooking my mother’s garden, and I would often join him. He sipped his thick Turkish coffee from a large white porcelain mug with the word Dad inscribed on it in scrolled lettering. I think my mother, sister, and I had given him the mug one Father’s Day, and he cherished it. He didn’t talk much, if at all, while we ate, and he always had a book to read.

As we sat quietly eating our breakfasts, he would look up at me occasionally and say, “Listen to the sounds of peace.” I once asked, “What are the sounds of peace?” And he said, “Just listen.” All I heard were a dog barking, tennis balls plopping on the gravel in the tennis court across the street, birds chirping, the wind in the trees.

It was the mid-1950s, only 10 years after the end of World War II, during which my father had been interned in a concentration or work camp in a place called Transnistria. He had sometimes mentioned Transnistria before he died, but it was only afterward, at the shiva after his funeral, that one of his old Romanian colleagues told me he had been in the camp — located between modern-day Moldova and Ukraine. That was when I realized that the sounds of peace were not something my father took for granted; they meant something even deeper than just the sounds of the birds and the trees.

When he told me to listen, he was appreciating with every fiber of his being the fact that he was alive and that my mother, sister, and I were there to savor life with him. To this day, I still take a moment to be quiet and listen to the sounds around me during my breakfast, outside on my patio, and feel gratitude for everything and everyone in my life.

So, to enhance your well-being, don’t practice gratitude only on Thanksgiving. Start every day by quietly turning to the four corners of your earth with gratitude for all you see and feel and hear, and end your day counting your blessings, instead of sheep. You’ll be activating those feel-good dopamine reward pathways and anti-pain endorphin pathways, reducing your stress response, and enhancing brain regions supporting your interpersonal relationships, to start your day on a path to staying well.

References

*Portions of this post are excerpted and condensed from: Sternberg, E.M. (2023) Well at Work:

Creating Wellbeing in Any Workspace. New York, NY: Little, Brown Spark.

Abdullah, N. (2023). The Scientific Effects Of Gratitude: A Review. Journal of Positive

Psychology and Wellbeing, 7(3), 192-205.

Fox, G. R., Kaplan, J., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. (2015). Neural correlates of gratitude.

Frontiers in psychology, 6, 1491.

Kyeong, S., Kim, J., Kim, D. J., Kim, H. E., & Kim, J. J. (2017). Effects of gratitude meditation

on neural network functional connectivity and brain-heart coupling. Scientific reports, 7(1),

5058.

Sternberg, E.M. (2009) Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-being. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Nanih Waiya: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanih_Waiya