Botanical Medicine

Is There Good Scientific Evidence?

There is a growing amount of evidence-based research supporting various botanicals, as this section will show.

There is currently a vigorous debate about whether botanical medicines are effective, and whether it is ever appropriate to use them in a modern medical setting. Some criticisms have stated that clinical studies of botanicals are of poor quality, limited by factors such as small sample sizes, limited duration of therapy, and poorly characterized products.

However, similar criticisms have been directed at clinical trials of pharmaceutical medicines. In fact, one recent study compared the quality of clinical trials using phytomedicines to matched trials using conventional medicines and came to the surprising conclusion that the method and reporting quality of Western clinical trials of herbal medicines was on average superior to that of conventional medicines (Nartley et al., 2007).

Evaluating the evidence

In evaluating any clinical study, whether of botanical or pharmaceutical medicines, it is important to pay attention to the quality and design of the study. Factors to consider include:

- Sample size (or number of people or medicines being tested)

- Length of the study

- Dose

- Goals of the study and how they were measured

- Nature of the medicine being investigated

In the case of botanical medicines, this last issue is particularly important since botanical medicines can vary in their composition, levels of active constituents, and the presence or absence of additional constituents that may display synergistic or antagonistic influences on the effect being measured (Spinella, 2002; Spelman, 2005). As a rule, synergy is not an issue in clinical studies of pharmaceutical medicines, but in clinical trials with botanical medicines, synergy can affect outcomes and complicate the interpretation of results.

It is also important to remember that a single study, no matter how well designed, is never definitive in itself. A single negative study does not necessarily negate the results of previous positive studies. In such circumstances, the study should be evaluated in the context of other similar studies. This is as true for studies of pharmaceutical medicines as it is for botanical medicines.

In addition, there are botanicals whose primary evidence comes from a long medicinal use. Although supporting evidence-based research may be limited in these cases, we should not ignore that these botanical medicines have been used for thousands of years, long before randomized clinical trials were conceived.

Botanical medicine used in common health conditions

People commonly use botanicals to maintain health and treat disease symptoms for all the functions listed below. In each of these cases, there is a considerable amount of scientific and clinical evidence related to the applications of botanical medicines. The following sections address each of these points. See also Why Do People Use Botanicals? for more references.

Cardiovascular and circulatory functions

Clinical studies indicate that botanical medicines have applications both for the maintenance of cardiovascular and circulatory health, and also for treatment of cardiovascular dysfunctions such as arrhythmia and mild hypertension (or high blood pressure).

Clinical studies indicate that botanical medicines have applications both for the maintenance of cardiovascular and circulatory health, and also for treatment of cardiovascular dysfunctions such as arrhythmia and mild hypertension (or high blood pressure).

For example, numerous clinical and animal studies document the efficacy of hawthorn as a cardiotonic. Cardiotonics help to improve blood supply to the heart, increase the tone of the heart muscle, stimulate cardiac output, dilate coronary arteries, stabilize blood pressure, prevent atherosclerosis (the accumulation of arterial plaque), and prevent or help improve congestive heart failure.

Many herbs used for cardiovascular health, such as hawthorn and gingko, have antioxidant properties, which may help prevent hardening of the arteries or other circulatory insufficiencies.

Some herbs used for cardiovascular health are commonly taken to lower cholesterol. Garlic is one notable example, and a number of clinical studies have shown that garlic is effective in moderately reducing serum cholesterol. However, a recent meta-anlysis of the clinical trials on garlic (Reinhart et al., 2009) showed that while triglyceride levels are modestly reduced, LDL levels are not decreased and HDL levels are not increased. So the use of garlic supplements to reduce cholesterol must be considered controversial until further investigations have clarified this issue.

Some herbs used for cardiovascular health are commonly taken to lower cholesterol. Garlic is one notable example, and a number of clinical studies have shown that garlic is effective in moderately reducing serum cholesterol. However, a recent meta-anlysis of the clinical trials on garlic (Reinhart et al., 2009) showed that while triglyceride levels are modestly reduced, LDL levels are not decreased and HDL levels are not increased. So the use of garlic supplements to reduce cholesterol must be considered controversial until further investigations have clarified this issue.

Digestive, gastrointestinal, and liver functions

Consumers frequently use botanical medicines to treat a variety of minor illnesses related to gastric and digestive functions.

Clinical research indicates that ginger is a very effective herb for nausea, indigestion, and minor gastric upsets.

Ginger is also effective for morning sickness in the early stages of pregnancy and for motion sickness.

Peppermint oil has demonstrated clinical efficacy for irritable bowel syndrome.

Many herbs are liver protective and restorative-they can help to protect a healthy liver and restore function to a liver that has suffered impaired functions due to disease or injury, such as cirrhosis, hepatitis, or exposure to hepatotoxic agents. The potential benefit of milk thistle in the treatment of liver diseases remains a controversial issue, with two recent review studies (Rambaldi, 2007 and Saller, 2008) coming to different conclusions. (The authors of both studies acknowledge that evidence for clinical benefits of milk thistle extracts exists and suggest more rigorous studies are needed to resolve these controversies.)

Endocrine and hormonal functions

Botanicals can also affect many types of hormonal functions, including reproductive hormones, insulin functions, adrenal functions, thyroid, and hypothalamic and pituitary functions. Botanicals affecting reproductive hormones and functions are discussed under the section on reproductive functions while those that affect insulin functions or carbohydrate metabolism are discussed under Metabolic and Nutritional Functions.

"Adaptogens" are a modern term for what traditional herbalists used to call "tonics," an herbal preparation that is taken daily to maintain balance and improve general health. Many so-called adaptogenic herbs, such as ginseng, owe much of their activity to stimulation of pituitary and adrenal activity. Still other botanicals are used to treat thyroid disorders.

Genito-urinary and renal functions

Consumers use botanicals for various genito-urinary and renal functions. We discuss references for the following:

Consumers use botanicals for various genito-urinary and renal functions. We discuss references for the following:

- Preventing benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Preliminary clinical studies suggested that the benefits of saw palmetto were comparable to those of prescription medications, such as finasteride. While a recent review has shown that urinary symptoms were not improved compared to the patients receiving placebo (Tacklind et al., 2009), studies on the potential of saw palmetto in BPH are ongoing. Other botanicals used in the treatment of BPH include nettle and African plum (Prunus africana syn. Pygeum africanum). Although moderate improvements in BPH symptoms were shown in preliminary trials, studies of longer duration in larger numbers of subjects are needed to determine their effectiveness.

- Disinfecting the urinary tract. Many botanicals are diuretics; they can help eliminate disease-carrying microorganisms from the urinary tract, and they can help prevent kidney stone formation and bladder inflammation resulting from bladder irritation-whether or not it's due to microbial infection. Others are effective urinary tract disinfectants. One that has been studied clinically and found effective for both prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections is cranberry, which may be taken as cranberry juice or in the form of concentrated cranberry juice solids.

Protecting or restoring the kidneys. A much smaller number of botanicals have been used traditionally for their protective or restorative effects on the kidneys. Botanicals with potential applications in renal diseases include milk thistle, green tea, and the reishi mushroom. In most cases, rigorous clinical studies of the efficacy of botanicals for kidney disorders are lacking, but the use is supported by folk medicine and by numerous pre-clinical studies in animal models.

Protecting or restoring the kidneys. A much smaller number of botanicals have been used traditionally for their protective or restorative effects on the kidneys. Botanicals with potential applications in renal diseases include milk thistle, green tea, and the reishi mushroom. In most cases, rigorous clinical studies of the efficacy of botanicals for kidney disorders are lacking, but the use is supported by folk medicine and by numerous pre-clinical studies in animal models.

Reproductive functions

Consumers use botanicals for various reproductive system functions, including:

Treating menopausal and PMS symptoms. Black cohosh and phytoestrogenic herbs, such as red clover, are examples of botanicals shown in clinical studies to be effective for treating menopausal symptoms and PMS. Estrogenic compounds, sometimes called phytoestrogens, are widespread in both botanical medicines and foods, such as soy.

Treating menopausal and PMS symptoms. Black cohosh and phytoestrogenic herbs, such as red clover, are examples of botanicals shown in clinical studies to be effective for treating menopausal symptoms and PMS. Estrogenic compounds, sometimes called phytoestrogens, are widespread in both botanical medicines and foods, such as soy.- Managing pregnancy. For example, ginger has been shown in clinical studies to be a safe, effective treatment for morning sickness in pregnancy.

Helping milk production. Some nursing women use herbs to induce milk production during lactation, or conversely, to reduce milk production during weaning. For example, Fenugreek is an herb that has been successfully used to induce lactation (Tiran, 2003; Gaby, 2002). For comprehensive information on the use of herbs during lactation, including safety information, see Humphrey, 2003.

Helping milk production. Some nursing women use herbs to induce milk production during lactation, or conversely, to reduce milk production during weaning. For example, Fenugreek is an herb that has been successfully used to induce lactation (Tiran, 2003; Gaby, 2002). For comprehensive information on the use of herbs during lactation, including safety information, see Humphrey, 2003.- Treating sexual dysfunction. Some herbs are considered aphrodisiacs and may have some applications in the treatment of sexual dysfunctions in both men and women. While these applications are well-supported by "folk knowledge" and practical experience, extensive clinical evidence is lacking, primarily because the studies simply have not been done. With respect to erectile dysfunction, a number of herbs and nutraceuticals have been suggested for treatment, including Yohimbine (an alkaloid from Pausinystalia yohimbe), Asian ginseng (Panax ginseng), Maca (Lepidium meyenii), and Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba). Clinical studies of these botanicals for erectile dysfunction, however, are sparse (MacKay, 2004).

While botanicals could theoretically be used to induce abortions or as contraceptives, the herbs widely sold as dietary supplements do not have these activities, and the use of herbs for these purposes is rare in our culture.

Immune functions, infections, inflammations, and cancer

Immune function is a large category with a wide range of applications for botanical medicines.

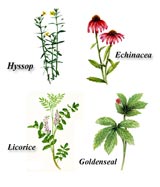

- Preventing infections from viruses and microbial pathogens. Various immune-stimulant botanicals, such as echinacea, have shown efficacy in some clinical studies to prevent infections from viruses and microbial pathogens. Other studies on echinacea's effectiveness have had more equivocal results. Strong immune system "tonics" such as the South American liana uncaria tomentosa, (cat's claw) have shown some success in clinical trials for the treatment of symptoms of viral infections, including HIV, herpes simplex, and h. zoster.

- Strengthening immune system. Besides the immediate benefit of preventing infections, immune-active botanicals, such as many of the "adaptogens" or tonics (e.g. ginseng, many Chinese medicinal mushrooms, or astragalus) can strengthen the immune system to help maintain general health.

- Reducing inflammation. Antinflammatory botanicals, of which there are many (examples include ginkgo, ginger, hawthorn, and St. John's wort) are useful in suppressing various immune functions involved in the inflammatory response. In many cases there is clinical evidence for the efficacy of these botanicals as anti-inflammatories.

- Prevention or treatment of cancer, as well as alleviating the side effects of chemo- or radiation-therapy. At some fundamental physiological level, cancer is basically caused by a failure of the immune system to recognize and destroy cancerous cells as they form in the body. Extracts of immune-stimulating medicinal mushrooms, such as reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) or turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), can be used as adjunct therapies to help maintain immune functions during radiation and chemotherapy.

Skin, muscular, and skeletal functions

Botanicals such as capsicum, witch-hazel, and calendula are used topically to support maintenance of the skin and integumentary system, and also for the treatment of problems with the skeletal musculature.

The most common topical uses for botanicals are as:

- Antimicrobials

- Anti-inflammatories

- Analgesics

- Astringents

- Demulcents

Botanicals have been used in this way for centuries, although their effectiveness has rarely been documented in formal clinical trials.

In many cases, the research supporting these uses is based on practical experience, rather than formal clinical trials, since the topical application of botanicals to treat minor skin diseases and maintain healthy skin is often classified as cosmetic use. Now there is a new generation of "cosmeceuticals" with claims that resemble medical claims. In a few cases, there are clinical studies demonstrating efficacy, for example, the use of Calendula creams to treat acute dermatitis in breast cancer patients receiving irradiation therapy.

Topical applications of botanicals can also effectively treat skin conditions, such as acne, psoriasis, and eczema. For each of these conditions, at least one clinical study demonstrating efficacy has been published.

Used internally, antioxidant botanicals containing flavonoids or oligomeric proanthocyanidins (OPCs), such as grape seed extract or pycnogenol, have been shown in animal and in vitro studies to support the health of collagen-containing connective tissues. (They do this by preventing oxidative damage, promoting cross-linking of collagen fibers, and preventing inflammation.) In the case of their anti-inflammatory properties, the evidence from pre-clinical studies is also supported by clinical studies.

Neurological, psychological, and behavioral functions

Botanicals that possess central nervous system activities or that indirectly affect psychological and nervous system functions are among the most popular dietary supplements.

Botanicals that possess central nervous system activities or that indirectly affect psychological and nervous system functions are among the most popular dietary supplements.

Consumers use botanicals to treat or manage a wide variety of psychological and neurological conditions. (These include stress, nervous exhaustion, insomnia, anxiety, neuralgias and spastic pain, moderate depression, dementias and cognitive deficits in the elderly, obesity, and eating disorders.)

Although results vary greatly, most of these applications are supported by at least a few clinical studies. In some cases, there are many studies (e.g. the use of St. John's wort for mild to moderate depression, or the use of ginkgo biloba for memory and cognitive deficits in the elderly).

Other applications of botanicals, such as kava or valerian in the treatment of seizure disorders or kudzu as an intervention for alcoholism, are promising, but clinical studies are rare. More research is needed in this area.

Metabolic and nutritional functions

Many types of botanicals and foods offer these types of functions.

Antioxidants

There is now abundant evidence that ingestion of adequate amounts of antioxidants in the diet can protect cells, tissues, and cellular components, such as DNA and cell membranes, from damage by so-called Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), many of which are produced as normal byproducts of metabolism. Antioxidants can also help to slow or prevent hardening of the arteries and eventual coronary heart disease--conditions that reduce the quality of life for the elderly.

Recent clinical trials show that taking single antioxidants, such as Vitamin C or Vitamin E, may not be as beneficial as eating a variety of fruits and vegetables that are rich in antioxidants. In fact, single antioxidant supplements might actually increase the risk of some diseases. The current consensus is that fruit and vegetables rich in antioxidants are best. However, if you would like to add supplements to your plan, here are some options:

- Flavonoid-containing herbs, such as ginkgo, hawthorn, and grape seed extracts

- Green tea, in its natural form or as a concentrated supplement

- Dark chocolate contains many of the same beneficial compounds, known as catechins

Including these antioxidant-containing herbs in the diet is unlikely to be detrimental, but consumers should not rely on antioxidant supplements alone.

Diabetes and Carbohydrate Metabolism

One application of botanical medicines in this area is to lower blood sugar in individuals who may be diabetic or pre-diabetic. Popular botanical medicines thought to have this effect include:

One application of botanical medicines in this area is to lower blood sugar in individuals who may be diabetic or pre-diabetic. Popular botanical medicines thought to have this effect include:

- American ginseng (Panax quinquifolia)

- Ayurvedic medicine (Gymnema sylvestre)

- Chinese bitter gourd (Momordica charantia)

- Green tea

In most cases, clinical investigations in well-designed trials have been minimal but encouraging, and better follow up studies are needed.

Adaptogens

Adaptogens are a class of botanical medicines that are thought to balance the metabolism, increase the body's resistance to physical and mental stress (often by modulating the body's "stress response" mediated by ACTH and adrenal corticosteroids), and stimulate cellular metabolism, digestive functions, and nutrient utilization. (See the section on Endocrine and Hormonal Functions for references related to Adaptogens.)

Botanicals for Weight Loss

Botanicals have been employed for weight loss, obesity, and blood sugar control. Ephedra is an example of a once-popular herb for weight loss, but it was recently banned by the FDA due to its potential to trigger adverse cardiovascular reactions, particularly in combination with caffeine, with which it is frequently formulated. Following the ban, green tea polyphenolics have become more popular for weight loss, and in fact, evidence of their efficacy has been reported in at least three clinical studies.

Nutritional Deficiency

With respect to nutritional deficiencies, the FDA has established special categories allowing health claims to be made for foods in cases where the claims are based on "authoritative statements" of a scientific body of the U.S. Government or the National Academy of Sciences. Examples of such claims include the importance of:

- Dietary fibers in reducing the risk of cancer and coronary heart disease

- Dietary calcium in preventing osteoporosis

- A low-fat diet in reducing the risk of congestive heart disease and cancers

- A low-sodium diet in reducing the risk of hypertension

Respiratory and pulmonary functions

Botanical medicines are particularly favored for treating or managing diseases of the respiratory and pulmonary system.

Respiratory Infections

Anti-infective and immune-stimulating botanicals, such as echinacea, may be taken internally or as a gargle to treat upper respiratory infections, chronic rhinitis, and chronic sinusitis.

Sore Throats

Botanicals, such as tinctures of sage, myrrh, goldenseal, calendula or echinacea are frequently employed as gargles to sooth, disinfect and heal sore or irritated throats. These herbs are often mixed with other herbs, such as licorice or slippery elm, to enhance the soothing properties.

Colds

- Lobelia or licorice are used as expectorants to promote the expulsion of phlegm

- Wild cherry bark or wild lettuce are commonly used to suppress coughs

- Hyssop and thyme are used to prevent bronchial spasms

- Demulcents (soothants), such as licorice, slippery elm bark, or marshmallow root, are utilized to soothe inflammations in the mouth and bronchial passages.

For most of these applications, extensive rigorous clinical studies have not been conducted. In many instances, such studies would seem unnecessary, since their efficacy has been demonstrated through decades and even centuries of practical experience in the hands of herbalists, folk healers, and even professional health practitioners.

In some cases, the effectiveness of botanicals to treat allergies has been well-documented in clinical studies. Skullcap and urtica (nettles) are used to treat allergies causing rhinitis, asthma, earaches, and even chronic conditions such as bronchitis and emphysema.

In other cases few or no clinical studies have been conducted to substantiate the claims for efficacy that are recognized and accepted by most herbalists.

Nartey, L., Huwiler-Muentener, K., Shang, A., Liewald, K., Jueni, P., Egger, M. (2007). Matched-pair study showed higher quality of placebo-controlled trials in Western phytotherapy than conventional medicine. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(8), 787-794.

Spinella, M. (2002). The importance of pharmacological synergy in psychoactive herbal medicines. Alternative Medicine Review, 7(2), 130-137.

Spelman, K. (2005). Philosophy in Phytopharmacology: Ockham's Razor versus synergy. Journal of Herbal Pharmacotherapy, 5(2), 31-47.

Cardiovascular and circulatory functions

Ackermann, R.T., Mulrow, C.D, Ramirez, G, et al. (2003). Garlic shows promise for improving some cardiovascular risk factors. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 813-824.

Coon, J.S.T., Ernst, E. (2003). Herbs for serum cholesterol reduction: A systematic review. The Journal of Family Practice, 52, 468-478.

Curnin, Y., Andriantsitohaina, R. (2005). Polyphenols as potential therapeutical agents against cardiovascular disease. Pharmacological Reports, 57, S97-S107.

Ferrari, C.K. (2004). Functional foods, herbs and nutraceuticals: Towards biochemical mechanisms of healthy aging. Biogerontology, 5(5), 275-289.

Frishman, W.H., Grattan, J.G., Mamtani, R. (2005). Alternative and complementary medical approaches in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Current Problems in Cardiology, 30(8), 383-459.

Gardiner, C., Lawson, L., Block, E., et al. (2007). Effect of raw garlic vs. commercial garlic supplements on plasma lipid concentrations in adults with moderate hypercholesterolemia. Archive of Internal Medicine, 167, 346-353.

Gardner, C.D., Messina, M., Lawson, L.D., Farquhar, J.W. (2003). Soy, garlic, and ginkgo biloba: Their potential role in cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 5(6), 468-475.

Meletis, C. (2003). Cardiovascular Disease. Alternative & Complementary Therapies, 158-162.

Pittler, M.H., Schmidt, K., Ernst, E. (2003). Hawthorn extract for treating chronic heart failure: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. American Journal of Medicine, 114(8), 665.

Reinhart, K.M., Talati, R., White, C.M., Coleman, C.I. (2009). The impact of garlic on lipid parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition Research Reviews, 22, 39-48.

Stout, C.W., Weinstock, J., Homoud, M.K., et al. (2003). Herbal Medicine: Beneficial effects, side effects, and promising new research in the treatment of arrhythmias. Current Cardiology Reports, 5, 395-401.

Digestive, gastrointestinal, and liver functions

Borelli, F., Izzo, A.A. (2000). The plant kingdom as a source of anti-ulcer remedies. Phytotherapy Research, 14, 581-591.

Boone, S., Shields, K. (2005). Treating pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting with ginger. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 39, 1710-1713.

Cappello, G., Spezzaferro, M., Grossi, L., Manzoli, L., Marzio, L. (2007). Peppermint oil (Mintoil[r]) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective double blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Digestive and Liver Disease, 39(6), 530-536.

Chrubasik S, Pittler M, Rougogalis B. (2005). Zingerberis rhizoma: a comprehensive review on the ginger effect and efficacy profiles. Phytomed.,12, 684-701.

Comar, K.M., Kirby, D.F. (2005). Herbal remedies in gastroenterology. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 39(6), 457-468.

Langmead, L., Rampton, D.S. (2001). Review article: Herbal treatment in gastrointestinal and liver disease-benefits and dangers. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 15(9), 1239-1252.

Liu, J., Manheimer, E., Tsutany, K., Gluud, C. (2003). Medicinal herbs for hepatitis C virus infection: A Cocharne hepatobiliary systematic review of randomized trials. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 98, 538-544.

Rambaldi, A., Jacobs, B.P., Gluud, C. (2007). Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.: CD003620.

Saller, R., Brignoli, R., Melzer, J., Meier, R. (2008). An updated systematic review with meta-analysis for the clinical evidence of silymarin. Forschende Komplementarmedizin,15, 9-20.

Tamayo, C., Diamond, S. (2007). Review of clinical trials evaluating safety and efficacy of milk thistle. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 6(2), 146-157.

Yang, Z.C., Yang, S.H., Yang, S.S., Chen, D.S. (2002). A hospital-based study on the use of alternative medicine in patients with chronic liver and gastrointestinal diseases. Amerian Journal of Chinese Medicine, 30(4), 637-643.

Endocrine and hormonal functions

Gaffney, B.T., Hugel, H.M., Rich, P.A. (2001). Panax ginseng and Eleutherococcus senticosus may exaggerate an already existing biphasic response to stress via inhibition of enzymes which limit the binding of stress hormones to their receptors. Medical Hypotheses, 56(5), 567-572.

Panossian, A., Wagner, H. (2005). Stimulating effect of adaptogens: An overview with particular reference to their efficacy following single dose administration. Phytotherapy Research, 19(10), 819-838.

Panossian, A. (2003). Adaptogens. Alternative & Complementary Therapies, 327-331.

Yarnell, E., Abascal, K. (2006). Botanical medicine for thyroid regulation. Alternative & Complementary Therapies, 107-112.

Genito-urinary and renal functions

Avins, A., Bent, S. (2006). Saw palmetto and lower urinary tract symptoms: what is the latest evidence? Current Urology Reports, 7, 260-265.

Bailey, D., Dalton, C., Daugherty, F.J., Tempesta, M.S. (2007). Can a concentrated cranberry extract prevent recurrent urinary tract infections in women? A pilot study. Phytomedicine, 14, 237-241.

Dreikorn, K. (2002). The role of phytotherapy in treating lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. World Journal of Urology, 19(6), 426-435.

Dvorkin, L., Song, K.Y. (2002). Herbs for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 36(9), 1443-1452.

Jepson, R.G., Craig, J.C. (2007). A systematic review of the evidence for cranberries and blueberries in UTI prevention. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 51(6), 738-745.

Lopatkin, N., Sivkov, A., Schlafke, S., Fun, P., Medvedev, A., Engelmann, U. (2007). Efficacy and safety of a combination of Sabal and Urtica extract in lower urinary tract symptoms-long-term follow-up of a placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial. International Urology and Nephrology, DOI 10.1007/s11255-006-9173-7.

Peng, A., Gu, Y., Lin, S.Y. (2005). Herbal treatment for renal diseases. Annals Academy of Medicine, 34(1), 44-51.

Tacklind, J., MacDonald, R., Rutks, I., Wilt, T.J. (2009). Serenoa repens for benign

prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD001423.

Yarnell, E. (2002). Botanical medicines for the urinary tract. World Journal of Urology, 20(5), 285-93.

Yarnell, E., Abascal, K. (2007). Herbs for relieving chronic renal failure. Alternative & Complementary Therapy, 13(1), 18-23.

Reproductive functions

Aubertin-Leheudre, M., Lord, C., Khalil, A., Dionne, I. J. (2007). Effect of 6 months of exercise and isoflavone supplementation on clinical cardiovascular risk factors in obese postmenopausal women: A randomized, double-blind study. Menopause, 14(6), 606.

Gabay, M.P. (2002). Galactogogues: Medications that induce lactation. Journal of Human Lactation, 18(3), 274-279.

Geller, S.E., Studee, L. (2005). Botanical and dietary supplements for menopausal symptoms: What works, what does not. Journal of Womens Health, 14(7), 634-649.

Geller, S.E., Studee, L. (2006). Soy and red clover for midlife and aging. Climacteric, 9(4), 245.

Hardy, M.L. (2000). Herbs of special interest to women. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 40, 234-242.

Humphrey, S. (2003). The nursing mother's herbal (The human body library) . Minneapolis, MN: Fairview Press.

Krebs, E.E., Ensrud, K.E., MacDonald, R., Wilt, T.J. (2004). Phytoestrogens for treatment of menopausal symptoms: A systematic review. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 104(4), 824-836.

Lethaby, A.E., Brown, J., Marjoribanks, J., Kronenberg, F., Roberts, H., Eden, J. (2007). Phytoestrogens for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4.

MacKay, D. (2004). Nutrients and botanicals for erectile dysfunction: Examining the evidence. Alternative Medicine Review, 9(1), 4-16.

Mahady, G.B., Parrot, J., Lee, C., Yun, G.S., Dan, A. (2003). Botanical dietary supplement use in peri-and postmenopausal women. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society, 10, 65-72.

Noe, J., Bove, M., Janel, K. (2002). Herbal tonic formulas for naturopathic obstetrics. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 327-335.

Ososki, A.L., Kennelly, E.J. (2003). Phytoestrogens: A review of the present state of research. Phytotherapy Research, 17(8), 845-69.

Tiran, D. (2003). The use of fenugreek for breast feeding women. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery, 9(3), 155-156.

Weier, K.M., Beal, M.W. (2004). Complementary therapies as adjuncts in the treatment of postpartum depression. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 49(2), 96-104.

Westfall, R.E. (2001). Herbal medicine in pregnancy and childbirth. Advances in Natural Therapy, 18, 47-55.

Immune functions, infections, inflammations, and cancer

Block, K.I., Mead, M.N. (2003). Immune system effects of echinacea, ginseng, and astragalus: A review. Integrative Cancer Therapy, 2(3), 247-267.

Groom, S.N., Johns, T., Oldfield, P.R. (2007). The potency of immunomodulatory herbs may be primarily dependent upon macrophage activation. Journal of Medicinal Food, 10(1), 73-79.

Kim, L., Wollner, D., Anderson, P., Brammer, D. (2004). Echinacea for treating colds in children. JAMA, 291, 1323.

McKenna, D., Hughes, K., Jones, K. (2002). Astragalus. Alternative Therapies, 8(6), 34-40.

Meletis, C., Barker, J. (2003). Medicinal mushrooms. Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 141-145.

Martin, K.W., Ernst, E. (2003). Antiviral agents from plants and herbs: A systematic overview. Antiviral Therapy, 8, 77-90.

Miller, S. C. (2005). Echinacea: A miracle herb against aging and cancer? Evidence in vivo in mice. Evidence Based Complementary Alternative Medicine, 2(3), 309.

Park, E.J., Pezzuto. J.M. (2002). Botanicals in cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Metastasis Reviews, 21(3-4), 231-255.

Ruan, Wen-jing, Lai, Mao-de, Zhou, Jian-guang (2007). Anticancer effects of chinese herbal medicine, science or myth? Journal of Zeijian University Science B, 7(12), 1006.

Seely, D., Mills, E.J., Wu, P., Verma, S., Guyatt, G.H. (2005). The effects of green tea consumption on incidence of breast cancer and recurrence of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 4(2), 144-155.

Taylor, J.A., Weber, W., Standish, L., et al. (2003). Efficacy and safety of echinacea in treating upper respiratory tract infections in children: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290(21), 2824.

Yarnell, E., Abascal, K. (2006). Herbs for curbing inflammation. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 22-28.

Skin, muscular, and skeletal functions

Ahmad, N., Katiyar, S.K., Mukhtar, H. (2001). Antioxidants in chemoprevention of skin cancer. Current Problems in Dermatology, 29, 128-139.

Baliga, M., Katiyar, S. (2006). Chemoprevention of photocarcinogenesis by selected dietary botanicals. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology, 5, 243-253.

Bedi, M.K., Shenefelt, P.D. (2002). Herbal therapy in dermatology. Archives of Dermatology, 138(2), 232-242.

Dattner, A.M. (2003). From medical herbalism to phytotherapy in dermatology: Back to the future. Dermatology Therapy, 16(2), 106-13.

Hon, K.L., Leung, T.F., Ng, P.C., Lam, M.C., Kam, W.Y., Wong, K.Y., Lee, K.C., Sung, Y.T., Cheng, K.F., Fok, T.F., Fung, K.P., Leung, P.C. (2007). Efficacy and tolerability of a Chinese herbal medicine concoction for treatment of atopic dermatitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Dermatology, 157(2), 357-363.

Koo, J., Desai, R. (2003). Traditional Chinese medicine in dermatology. Dermatologic Therapy, 16(2), 98-105.

Mantle, D., Gok, M.A., Lennard, T.W. (2001). Adverse and beneficial effects of plant extracts on skin and skin disorders. Adverse Drug Reactivity Toxicology Review, 20(2), 89-103.

Pommier, P., Gomez, F., Sunyach, M.P., D'Hombres, A., Carrie, C., Montbarbon, X. (2004). Phase III randomized trial of Calendula officinalis compared with trolamine for the prevention of acute dermatitis during irradiation for breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(8), 1447-1453.

Wolff, H.H., Kieser, M. (2007). Hamamelis in children with skin disorders and skin injuries: Results of an observational study. European Journal of Pediatrics, 166(9), 943.

Neurological, psychological, and behavioral functions

Fava, M., Alpert, J., Nierenberg, A.A., Mischoulon, D., Otto, M.W., Zajecka, J., Murck, H., Rosenbaum, J.F. (2005). A double-blind, randomized trial of St John's wort, fluoxetine, and placebo in major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(5), 441-447.

Gardner, D.M. (2002). Evidence-based decisions about herbal products for treating mental disorders. Journal of Psychiatry Neuroscience, 27, 324-333.

Gelenberg, A.J., Shelton, R.C., et al. (2004). The effectiveness of St. John's Wort in major depressive disorder: A naturalistic phase 2 follow-up in which non-responders were provided alternate medication. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(8), 1114-1119.

Howes, M.J., Perry, N.S.L., Houghton, P.J. (2003). Plants with traditional uses and activities relevant to the management of Alzheimer's disease and other cognitive disorders. Phytotherapy Research, 17, 1-18.

Kasper, S., Anghelescu, I.G., Szegedi, A., Dienel, A., Kieser, M. (2006). Superior efficacy of St John's wort extract WS 5570 compared to placebo in patients with major depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial [ISRCTN77277298]. BMC Med., 4, 14.

Kienzie-Hom, S. (2002). Herbal medicines for neurological diseases. Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs, 3, 763-767.

Kirsch, I. (2003). St. John's wort, conventional medication, and placebo: An egregious double standard. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 11, 193-195.

Lau, F.C., Shukitt-Hale, B., Joseph, J.A. (2007). Nutritional intervention in brain aging: Reducing the effects of inflammation and oxidative stress. Subcell Biochem., 42, 299-318.

Lukas, S.E., Penetar, D., et al. (2005). An extract of Chinese herbal root kudzu reduces alcohol drinking by heavy drinkers in a naturalistic setting. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(5), 756.

Wheatley D. (2005). Medicinal plants for insomnia: a review of their pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability. J Psychopharmacology, 19(4), 414-421.

Metabolic and nutritional functions

Chantre, P., Lairon, D. (2002). Recent findings of green tea extract AR25 (Exolise) and its activity for the treatment of obesity. Phytomedicine, 9(1), 3-8.

Diepvens, K., Westerterp, K.R., Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. (2007). Obesity and thermogenesis related to the consumption of caffeine, ephedrine, capsaicin, and green tea. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol., 292(1), R77-85.

Dog, T.L., Riley, D. (2003). Management of hyperlipidemia. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 9(3), 28-40.

Engler, M., Chen, C., et al. (2004). Flavonoid-rich dark chocolate improves endothelial function and increases plasma epicatechin concetrations in healthy adults. J Am Coll Nutr., 23(3), 197-204.

Ferrari, C.K. (2004). Functional foods, herbs and nutraceuticals: Towards biochemical mechanisms of healthy aging. Biogerontology, 5(5), 275-289.

Fukino, Y., Ikeda, A., et al. (2007) Randomized controlled trial for an effect of green tea-extract powder supplement on glucose abnormalities. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 62(8):953-60.

Melton, L. (2006). The antioxidant myth: A medical fairy tale. New Scientist, 5(2563).

Miller, N., Ruiz, Larrea, M. (2002). Flavonoids and other plant phenols in the diet: Their significance as antioxidants. Journal of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine, 12, 39-51.

Kligler, B., Lynch, D. (2003). An integrative approach to the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 9(6), 24-32.

Moro, C.O., Basile, G. (2000). Obesity and medicinal plants. Fitoterapia, 71(1), S73-82.

Yeh, G.Y., Eisenberg, D.M., Kaptchuk, T.J., Phillips, R.S. (2003). Systematic review of herbs and dietary supplements for glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes Care, 26(4), 1277-1294.

Respiratory and pulmonary functions

Brinckmann, J., Sigwart, H., van Houten, Taylor, L. (2003). Safety and efficacy of a traditional herbal medicine (throat coat) in symptomatic temporary relief of pain in patients with acute pharyngitis: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 9(2), 285-298.

Hubbert, M., Sievers, H., Lehnfeld, R., Kehrl, W. (2006). Efficacy and tolerability of a spray with Salvia officinalis in the treatment of acute pharyngitis - a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with adaptive design and interim analysis. Eur J Med Res, 11(1), 20.

Li, X-M. (2007). Traditional Chinese herbal remedies for asthma and food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 120(1), 25-31.Singh, B.B., Khorsan, R., et al. (2007). Herbal treatments of asthma: A systematic review. Journal of Asthma, 44(9), 685.

Szelenyi, I., Brune, K. (2002). Herbal remedies for asthma treatment: Between myth and reality. Drugs Today, 38(4), 265-303.

Wen, M., Wei, C., Hu, Z., et al. (2005). Efficacy and tolerability of anti-asthma herbal medicine intervention in adult patients with moderate-severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immun, 517-524.